Drummer Spencer Dryden, who died of colon cancer in 2005, played a role in fifties rock, then joined Jefferson Airplane and performed with the group on all of its key albums and at Monterey Pop, Woodstock, and Altamont. He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame with the Airplane in 1996. He quit the group in 1970 and signed on with New Riders of the Purple Sage. Four years later, in the summer of 1974, I interviewed him at length in upstate New York and published the following article.

New Riders of the Purple Sage drummer Spencer Dryden remembers the five years (1966–70) that he spent with Jefferson Airplane as a mixed bag of good times and absurdity. But in the year before he left the group, it was the weirdness that predominated.

He recounts an incident that seems to sum up the period. The members of the Airplane were driving to a gig in Anaheim, California and they got stuck in a traffic jam—which, ironically, had been caused by their own promise to perform.

“I was looking out the window of the car and saying, ‘Are these people all here for us and what do they expect? What do they want and where am I and who am I?'”

By the time these questions flashed into his mind, Dryden had been navigating through the calms and storms of a wide-ranging musical career for about 15 years. He had appeared in films like Rock Around the Clock and Rock, Rock, Rock and had drummed in rhythm and blues and jazz groups. He had authored the beat for a band that was one of the chief exponents of the “San Francisco sound.” And he had been a major participant at Woodstock, Altamont, and other landmark events of the 60s.

Few were surprised when, in 1970, he joined New Riders of the Purple Sage after a post-Airplane “retirement” that had lasted only three months. Music had been the major force in Dryden’s life at least since he quit college, almost two decades earlier, to pursue what was already a full-time career.

How did it feel when you first started to make it as a musician?

Here I was, working six or seven nights a week in clubs and bars and teaching drums part-time. I was making a living doing what I was going to do. And my mother’s saying, “Spencer, be a doctor, be a psychiatrist.” That never worked. And I just ended up figuring, Christ, man, I’m making $150 a week. And like guys that I knew were making $85 or $90 a week working for Packard-Bell or pumping gas. I just figured I’m really doing it. Which blew me out as much as my mother, man. You know . . . in two different ways!

How did you happen to join Jefferson Airplane?

They started with a drummer named Jerry Peloquin, but he lasted about two weeks. And the guy they recruited next—Skip Spence—was really a guitar player. But Marty [Balin] insisted, “You’re gonna be our drummer.” So they bought him a set of drums and he picked up really fast. But at the time, man, Skip was just a little bit crazy and he said, “You know, it ain’t me.”

That’s when you came into the picture?

Right. I guess there weren’t many drummers that they knew of in San Francisco at the time and so their manager, who had had some dealings in the Los Angeles area—which is where I was—phoned up some of the studio guys there. And they said, “Here’s a cat, man, and he’s got long hair and he’s done a whole lot of work.” So they called me and I was really interested. I went up [to San Francisco], did the audition, and, all of a sudden, I was in this part of town I’d never been in, which was Haight Ashbury.

How did it impress you?

I saw what seemed like just hundreds of long-haired people. And I was coming from L.A., where long hair was something that just musicians or guys who wore wigs on weekends had. Here were people that were real and not only that, they were contributing to some kind of community and they were actually making things. They were all artists. It was the real thing and it was just like you read about it, folks, and there it was and it brung me out. The guys in the Airplane, who I had just met, started taking me around to places and I met a whole bunch of musicians and everybody seemed high.

Grace Slick wasn’t in the group yet, right?

Right. She joined shortly after I did. It was very weird, ’cause the band that I’d been in [the Ashes, later called Peanut Butter Conspiracy] had a girl singer—it had the same lineup as the Airplane—and she had become pregnant. Now I happened to join the Airplane, who had a pregnant singer, Signe Andersen. She was just about ready to deliver, so the first gigs I ever worked with the Airplane were without her. And later, it was just a drawback, traveling with the baby. But it was a drag, ’cause she was a good singer.

However, at the same time, there was a band called the Great Society, and Grace sang with them. We’d played gigs with the Great Society and we always loved their music. And when it got to the point where we figured it wouldn’t work with Signe anymore, Grace was asked, one night at the Fillmore, “Hey, you want to sing with our band?” She talked to Jerry [Slick, then Grace’s husband and drummer with the Great Society] and he thought it’d be cool and she thought it’d be cool.

And we had like one show, Signe’s farewell thing—and there were tears and an award for her and all that—and then we started rehearsals with Grace. She brought two of her songs from the Great Society, “Somebody to Love” and “White Rabbit.” And both of those tunes were ones that we had always gotten off on.

Darby Slick [Jerry’s brother] wrote—

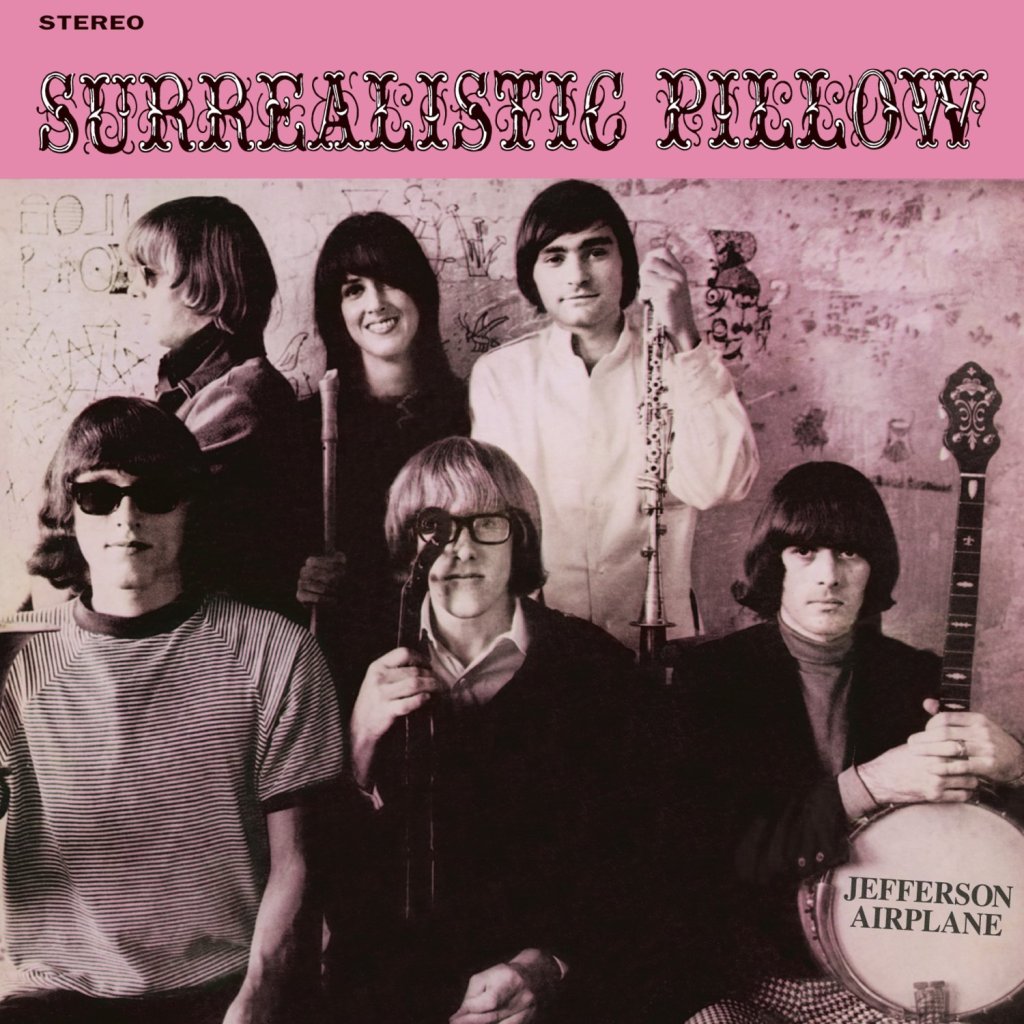

“Somebody to Love,” right. And both of those songs ended up on Surrealistic Pillow, the second Airplane album and the first that I played on.

There have been stories about hassles with RCA concerning those early records.

There were points with RCA that we fought over. We had renegotiated at least a couple of times. Everything was kind of growing at once. And we, of course, thought very liberally and to them, it was radical thinking. There were things that were X’d off records, tunes that were taken off. Words that were zipped, pictures that we drew on the Baxter’s album they blacked out, and if you pull out that record sleeve, you’ll see big ink going across stuff. The reason for that was that they saw things in there that we didn’t even mean. And if the record was going to be released, it had to go. And finally, I think, everybody kind of grew up.

What changes did you go through when the Airplane began to achieve success?

Well, that dream is always a dream, and when it becomes reality, nobody really knows how to deal with it. We didn’t. Bill Graham, who was then our manager, didn’t know how to deal with it, either. He did to the degree that he has done what he’s done but we all fell down on the way up. There’s nobody that got on the escalator and didn’t take a fall or two. We climbed, and sometimes a little bit faster than we were ready to deal with. And it became kind of weird. I was starting to feel the pressure. I think everybody was.

And at the end of ’69, of course, was the Altamont thing, and that was kind of foreboding. Just prior to that had been Woodstock, which to me, man, seemed to blow it totally out of proportion, but it was a gas. I mean, it was something you don’t repeat. Just like you don’t repeat the be-in and you don’t repeat Monterey. They’ve never happened again . . . although it did come close with that Watkins Glen thing. And it’s good to see that many people get out and have fun.

Can you tell me about your experiences at Woodstock?

I got there about 3 o’clock in the afternoon and took acid as everybody did. And by about 4 o’clock, I was sitting on the stage, which was like a ship. The wind was blowing into this huge screen in back of us, like a sail, and I was sure, man, that this thing was moving. I thought it was going to fall and people were saying, “Get off the towers, the towers are going to collapse.” And I couldn’t get up from the stage.

What time were you scheduled to play?

Around 4 o’clock. So I had supposedly dropped [acid] in time to do what I was gonna do. But time went on; it was 8 o’clock. “Sly isn’t here yet and the Dead just got set up.” So, OK, that’s cool. And Janis. And they asked us, “Can the Who go on?” Sure, man, just so long as we get to play when the sun comes up. And so it got to be 5 in the morning. The Who were still going through like half their Tommy trips. And we’re all by the side of the stage. I’m still wiped out of my mind, but I’ve peaked and I’m coming down. We’re still all kind of giggling, though, and everybody’s just physically drained. And the Who are doing this great set, just great set.

And finally, like 5 or 6 in the morning—the sun had come up during the end of the Who’s set—we got on. Half of the people are flaking out, but at least it’s not raining. The guy who was running the cameras and the guy that was doing the sound for the film fell out. ‘Cause they had been going for like 18 hours, since the previous noon. So we weren’t in the film, man. The guys fell out.

When did you decide to leave Jefferson Airplane?

The next year, 1970. I finally got to the point where it was, “I don’t want to play music anymore; it’s too crazy.”

Have you done anything with the group since?

I did one cut on Bark, but I’m not credited for that; it was “Lawman,” if anybody gives a damn. They put out The Worst of, where I guess I’m on 10 cuts. And I did one thing for Paul [Kantner] and Grace on their second album.

Sunfighter.

Yeah, I think I did “Earth Mother” and I was mixed out of the whole tune except for the last eight bars, but that doesn’t matter, because I wasn’t a member of the band.

What were you doing after you left the Airplane?

I moved to Sausalito from San Francisco, across the bridge. And I put my drums in the basement. Meanwhile, I was looking at boats, because Sausalito is a boating community; and all of a sudden, I really wanted one. I found a captain’s gig, which is one of those little boats that go down the side of a battleship or something that takes the captain to and from shore. I spent the whole summer down at the boatyards from about 7 in the morning to about 8 at night—as many daylight hours as I could get in—cleaning transmissions, scraping the hull, and that stuff. And that was my whole life for the summer of 1970.

Then Nicky Hopkins gave me a call. Nicky said, “Do you want to do a radio commercial? And Nicky’s a friend, a dude that I respect, so I said sure. We went down and made a commercial. Then Nicky called me again about a week later to do a Dial soap commercial. So all of a sudden, man, I keep bringing my drums out and putting them in the bus, going down into the city, and I hadn’t done that for years.

For years?

Well, like when I joined the Airplane, in the original days, we all used to load our own equipment, and then the thing with “quippies” came in; you had guys doing that stuff for you. I’d never had that done in my life. I was embarrassed. There’s some guy doing my gig. Part of my gig was always to unload my drums, set ’em up, figure ’em out, and play ’em. Now they got guys to do that for you. It was weird. But I guess it means a bigger family and there’s lots of guys that want to hang around and like to travel with you, and they can cover for you when you do the big gigs. Like you start breaking stuff and they’re there with something for you and so it’s a groovy trip.

But now, for these radio ads, you were back to doing the whole thing yourself.

Here I was, man, going back to the old days. Hauling my drums down there . . . going home and getting my union check . . . paying my dues.

Then one day, the Bear [Grateful Dead soundman] and McIntire [manager of the Dead and the New Riders] came over. And they said, “Look, man, do you dig the New Riders?” I said I’d never heard of them. So they said, “You simply gotta dig this band.” All right, two weeks later, they’re playing the Avalon, and I went and got turned on.

A while later, I heard they were making a record and I went down, heard them a couple times again in the studio. Then a little bit of time went past and I got another call: “Will you come down to Wally Heider’s [San Francisco recording studio] and listen to what we got?” So I went down.

Did you like what you heard?

It was not that good. And I’m a very blunt dude. I said, “Listen, I’ve heard you guys play better and, for Chrissake, this band of all bands, you’ve got it right there . . . let’s make a good album, OK?”

“Well, you know Mickey [Hart, New Riders’ original drummer] is leaving.”

“No, I didn’t know Mickey was leaving.”

“Will you play drums?”

So I started playing drums with them and we made the album.

Which cuts do you drum on that first record?

I think there’s 12 tunes and Mickey played on two of ’em, “Last Lonely Eagle” and “Dirty Business.” And I never could’ve cut Mickey’s parts, man. On the other ones, it was just that the whole band wasn’t together and I said, “Well, let’s go in and try it again.” We did it in three days, cutting the basics. We spent about two more weeks putting the overdubs in. And after that . . . I guess I ended up being in the band.

Let’s talk about your latest studio album.

The name of it is Panama Red, but if you take Columbia’s lawyers’ version of it, it’s called The Adventures of Panama Red. Because they certainly didn’t want anything relating to drugs. But as far as I’m concerned, the name of it is Panama Red. Which is damn well what I wanted it to be. I kept saying, “Look, Panama Red is a dude. He’s this guy, all right? And he goes around and does funny things. You just have to dig him for who he is.” Uh-uh, no, everybody says we have to call it Adventures of so everybody knows. And the cover of the album is a picture of the guy. There he is, man; he’s called Panama Red. I mean, if I wanted grass, I would’ve had a picture of grass, right?

Where’s the New Riders’ music going? You seem to have the two sides, the “Willie and the Hand Jive” sort of thing and the more—

The bam, ba-bam, ba-bam—

Yeah, like “Linda,” the country stuff.

It’s going both ways, ’cause we have different writers in the band who hear different music.

Are you writing anything?

Yeah, I wrote one tune for the Panama Red album. And my songs are country, but they’re country with a slam. In other words, there’s a definite beat to it; it isn’t light and airy. But it’s like the country lament, telling your tale of woe. But that’s just me.

[A young man wearing jeans and a denim jacket—covered with New Riders and other patches—enters the room.]

This is Bruce, by the way. Bruce is . . . somebody, man, what can I tell ya? I had this beautiful set of custom-made drums and about two and a half years ago, the guys left our drums up in Bangor, Maine. And somehow . . . we’re playing the Fillmore East about two weeks later and I’d lost my drums, man. I was paying for newspaper ads, radio ads: “Gimme back my drums, please.” Here comes this dude up to the front door of the Fillmore, says “Spencer! Spencer!” Brooklyn Fox Fabian voice. “I got your drums.” I said, “No?” He said, “Yes!” And I said, “Let’s see ’em,” and there they were, man.

I think I saw your ad.

I’m telling you, man. This dude and a couple of his friends. And ever since then, man, they’ve been traveling with us.

How’d you find the drums, Bruce?

Bruce: They were underneath the stage.

Spencer: And all the straight dudes that we asked to look around, all the powers-that-be, they couldn’t find the drums. It took a friend of the band to do it.

How have audiences been responding to the New Riders these days?

Our band is a little bit strange. We take a little time to bring ’em out. We start one way and if we’re doing a long set, which we often do, we go to a point and take a break to regroup our forces, which is something we learned from the Dead. It’s like playing football—half-time.

And we come back, man, and the steamroller starts. By the time we hit the last of the two or three hours, if those people aren’t boogieing, there’s something wrong somewhere. That’s what I always look for. I want it and I think that’s what the people come for; they want it. And if there’s something you both want, all you have to do is just push a little bit harder . . . and that will maybe answer your earlier question about how is it possible . . . everybody has to want it.

But I’ve noticed a lot of cynicism lately from both bands and audiences.

Everybody’s afraid. What are you gonna do, man? Things have changed. You know, all that beauty was shattered. Not all at once, but it was shattered fairly fast from its growth to its destruction. It was pretty obvious what happened, man. Like all the idealism just doesn’t work in today’s society. You have to work a little bit harder, a little bit more underground. You have to compromise to make that kind of thing eventually come true.

And you’re optimistic?

The thing is that it was shown; it was shown and taken away. Now for the people it was taken from . . . it wasn’t meant to be shown to them. For the people that still remember it, it’s still there. So what you need is growth from the people that saw it. I think that’s eventually gonna come. And I’m not really an idealist anymore. I’m cynical and I have my rank sense of humor, etc. There’s some things I think are really messed up and I don’t know what to do about them. But I just keep figuring, man, there’s so many other people that I’ve come in contact with that have a belief and if you keep growing it . . .

But the next time, we’re not gonna grow it overground. ‘Cause that’s what killed it. You give it to the media, man, and forget it, it’s dead. All you gotta do is turn on one other person. And instill that stuff in your children, if you have any. They keep growing into new people. It’s like a chain letter, man. And the good feeling gets spread around.

In any case, you seem to be feeling good tonight.

See, I’m not under pressure. A lot of groups, man, will come in like 10 minutes before showtime and they’re wired to the fucking gills and they get it on and get off and go away. I’ve been here for like five hours and I don’t have to go on for another 40 minutes. People here have fed me, man, given me something to drink, and I really don’t have anything to do except dig some music and go on and do whatever you have to do for the people.

I was backstage and toured east coast with the New Riders , a bunch , during 1973 and 1974… then i moved to California in the fall of 1974 and didnt go to a new riders show for decades, til around 2006, or so, at the Crystal Bay Club, in Lake Tahoe ,, boy was that a kickass show . Loved it. Talk about dancing…everybody was on their feet….The only original members were David Nelson and Buddy Cage. Marmaduke was very ill in 2005, and living in Mexico. I know this because our friend tried to hire the New Riders for his 50th in JUly 1975, and Marmaduke was very ill..So the agent got Jefferson Starship , with Paul Kantner, to play, instead, and that did not disappoint, with Paul Kantner opening the show, with Wooden Ships.

LikeLike

[…] and David Nelson on vocals and guitar, Buddy Cage on pedal steel, and Jefferson Airplane alumnus Spencer Dryden on drums. And, as evidenced by Hempsteader, the band could still raise a ruckus onstage with its […]

LikeLike

[…] and David Nelson on vocals and guitar, Buddy Cage on pedal steel, and Jefferson Airplane alumnus Spencer Dryden on drums. And, as evidenced by Hempsteader, the band could still raise a ruckus onstage with its […]

LikeLike