Several albums in Bruce Springsteen’s discography have proven particularly significant, including 1982’s Nebraska, which showcased a dramatic reversion to unadorned folk, and 1984’s Born in the U.S.A., which turned him into a global superstar. But the most pivotal chapter in his career came with his third LP, Born to Run, which his label released 50 years ago, in August 1975.

That album evidenced a quantum leap in Springsteen’s music and transformed him from a struggling potential has-been into a major force in the industry. The record not only looms large in his discography; it’s one of the most famous albums of the entire rock era by any artist. So, it’s no surprise that Springsteen named his autobiography after it—or that a new book is devoted entirely to its creation.

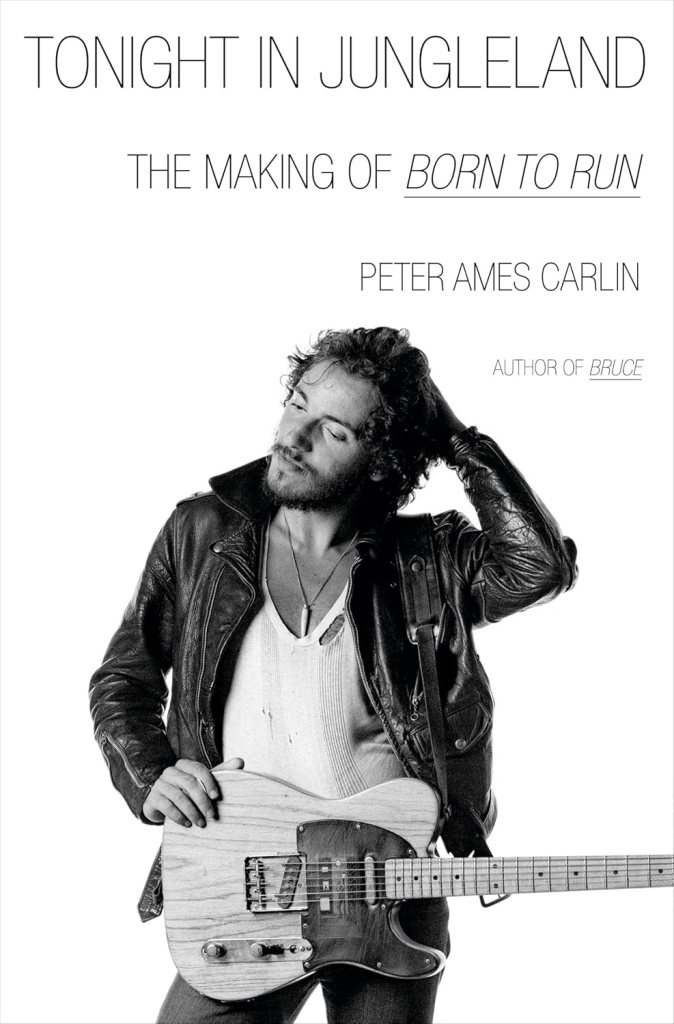

Called Tonight in Jungleland: The Making of Born to Run, the volume is the work of Peter Ames Carlin. Carlin already knew a thing or two about his subject going into the project, having published Bruce, an acclaimed Springsteen biography, in 2012. For this new book, he conducted fresh interviews with the artist and all the surviving members of the E Street Band, manager and co-producer Jon Landau, original manager and co-producer Mike Appel, session musicians, and others. Carlin also spoke with saxophonist Clarence Clemons a little before he died in 2011. The result is a revealing look at the period preceding Born to Run’s creation, the state of Springsteen’s career at the time, and the recording of each track on the album.

There’s a lot here about the music, but just as much about the record business and the challenges it presented. As the book makes clear, this was a make-or-break LP for Bruce, whose future before its release was much more uncertain than many listeners today might realize. His first two albums had sold poorly, and Carlin reports that for quite a while, Columbia executives seriously considered dropping him from the label.

At one point, moreover, Springsteen’s finances were so depleted that he couldn’t afford to hire the musicians he needed for the new album. Appel, who was as fanatically dedicated to the cause as Bruce himself, “swallowed hard and said okay, he’d figure it out,” writes Carlin. “He knew of only one pool of money he hadn’t tapped yet, and so he went to the bank that held his children’s college savings accounts and took every penny.”

I spoke with Bruce in January 1974, two months after his second album came out, and can attest to how dire his situation was. He spent much of our conversation describing his financial woes. “I ain’t makin’ that much money,” Springsteen told me. “I’ve got some great musicians in my band, and I’m payin’ them terrible money. I pay myself the same, but it’s terrible for me, too. I mean, we’re barely makin’ a livin’, barely scrapin’ by.’”

But Springsteen made clear to me that he believed in his work and planned to continue, regardless of whether he achieved commercial success. “This is it for me,” he said. “I got no choice. I have to write and play. If I became an electrician tomorrow, I’d still come home at night and write songs. If you can choose, you might as well quit. But if you have to, you have to.”

That determination comes through loud and clear in Carlin’s book, in which he describes the painstaking process that led to Born to Run. Springsteen had gargantuan ambitions and wanted the album to be not merely excellent, but the best rock record ever made. So, writes Carlin, “Every note and word mattered. The silence between the notes and words mattered. The length of the silence separating the songs mattered a lot.”

There were endless arguments among Bruce, his musicians, and his co-producers over song selections, arrangements, takes, tempos—you name it. And there were more conflicts in Springsteen’s head. When Clemons delivered his sax solo in “Jungleland,” for example, “Bruce listened, smiled and nodded, loved it,” writes Carlin. “Told him to do another. Terrific! Now do another. It went on like that for hours.” Springsteen even got heavily involved in discussions about what the album cover should look like.

Then, when it was all over, and Bruce heard the final mix, Carlin reports, he lashed out “at everyone in sight, until he finally shook his head. ‘I dunno, man, maybe we should just scrap it. Toss this shit and start over.’”

He wasn’t kidding. Engineer Jimmy Iovine showed up with an acetate copy, suggested that it might sound a bit different, and took Bruce off to listen to that. After they did, writes Carlin, Springsteen returned to his hotel, threw the acetate into its swimming pool, “stalked into his room, threw open the door, and slammed it shut behind him.” Fortunately, Appel and Landau later convinced him to proceed with the release.

It’s quite a story, and Carlin tells it impressively well—especially given that, as he says in a note at the end of the book, “I had to report and write the whole thing within a few months.” There are occasional hints of the rushed schedule: he repeats himself a few times, telling us twice, for example, about Appel’s use of his kids’ college money and about how the cover of Springsteen’s first album came to be. He also has a habit of mentioning the blazing fireplace in the room whenever he discusses a September 2024 interview he had with Bruce, and he slips a bit of arguably purple prose into one such reference.

But these are quibbles regarding a well-researched and expertly written book. If you care about Springsteen’s music, you’ll likely find it hard to put down.

The book is available here.

Two Notable Reggae Albums

Writes Ralph Sall, producer of a newly issued eponymous album from the Mighty Rootsmen: “I thought, what could I do in the reggae sphere, since I’ve always been such a big fan? Could I make a Traveling Wilburys of reggae? And who could I get to do it?”

Turns out he could get some of the biggest names in the genre, including Toots Hibbert of Toots and the Maytals, Gregory Isaacs, former Black Uhuru frontman Mykal Rose, and singer Luciano. Also on hand is the famed rhythm section consisting of drummer Sly Dunbar and bassist Robbie Shakespeare, who can be heard on umpteen classic reggae albums, not to mention recordings by artists such as the Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan.

Like many reggae outfits, this one focused on reinterpreting American hits. The Mighty Rootsmen includes 10 tracks, among them strong covers of such numbers as Cat Stevens’s “Peace Train,” Badfinger’s “Come and Get It,” and the Eagles’ “Take It Easy.” As if there weren’t enough star power in the band, Steve Miller guests on a cover of his “Fly Like an Eagle,” and the Heartbreakers’ Mike Campbell plays on a version of Tom Petty’s “I Won’t Back Down.”

Unfortunately, there will be no sequel to this set: though just released, it was recorded in 2010, then “put on a back burner as other projects took precedence,” according to the liner notes. Meanwhile, many of its key participants have died.

Like The Mighty Rootsmen, a new self-titled album from the Kingston Lions was produced by Ralph Sall and contains old (circa 2008) recordings. This CD features luminous Jamaican session musicians and a program consisting of excellent reinterpretations of some of reggae’s biggest hits.

Among the 14 covers on The Kingston Lions are four numbers that garnered fame on the stellar soundtrack of The Harder They Come: the Melodians’ “Rivers of Babylon,” the Slickers’ “Johnny Too Bad,” the Maytals’ “Pressure Drop,” and Keith & Tex’s “Stop That Train” (aka “Hold Your Brakes”). Other selections include “Israelites,” which in Desmond Dekker’s original version made the Top 10 on American charts in 1968; Dandy Livingstone’s “Rudy, a Message to You,” which has also been memorably covered by the Specials; and “Wonderful World, Beautiful People,” which gave Jimmy Cliff a major UK hit in 1969.

The Mighty Rootsmen is available on vinyl here and on CD here. The Kingston Lions is available on vinyl here and on CD here.

Discover more from By Jeff Burger

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.